colorism is a particular bullet

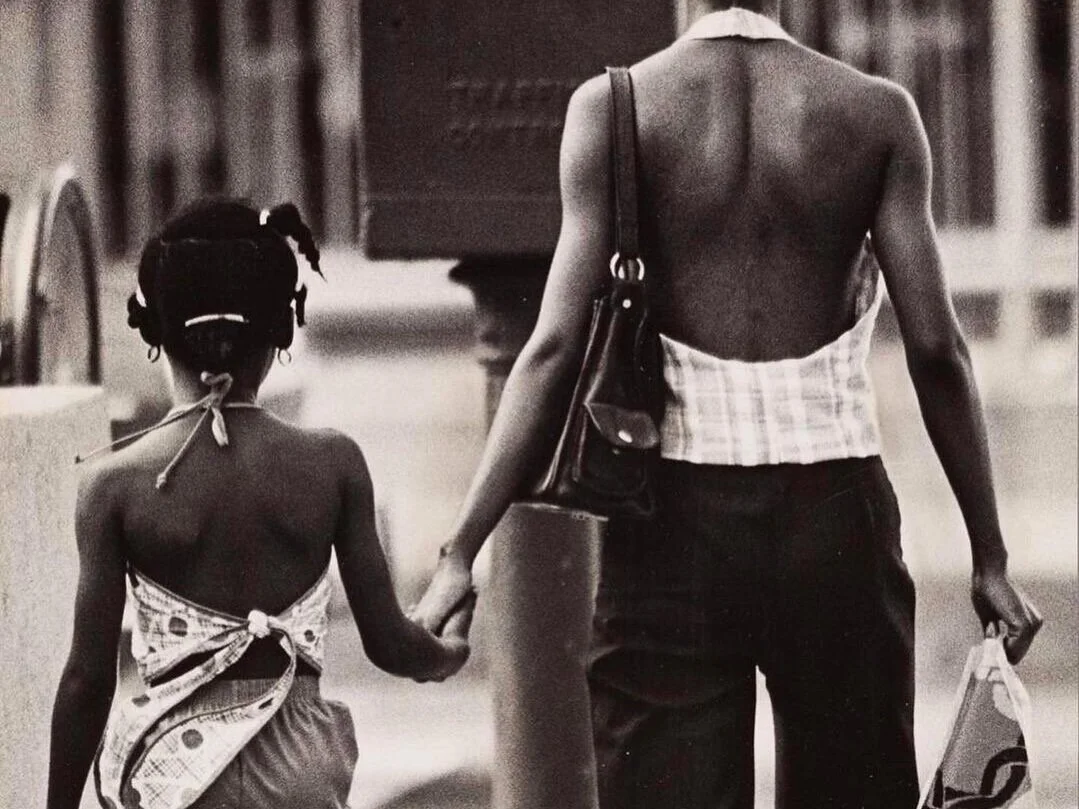

I don’t think there’s ever been in a moment in my life when I wasn’t reminded that I’m invisible, a shadow — only ever visible at the right time, from the right angle, while underneath a glaring light. When I was a young adolescent, I remember my childhood peers telling me to not play hide and seek in the dark because no one would find me, making the game unfair for the rest of them. In middle school, I remember being told countlessly that I would be the “girl” to be with if I didn’t remind everyone of tar. I remember thinking that a bath filled with bleach would be the thing to save me. That if I could just crawl out of this body and slip into a new skin that I’d finally be recognized as beautiful, as brilliant, as a person that people could see as whole, and present, and alive. This is what it’s like to live as a dark-skinned person yearning to be seen.

Many of us have been misinformed about the realities of colorism. When people hear about anti-Blackness, usually named as racism, people know that of the consequences, death is the most frequent. When people hear about colorism, people think that of the consequences, desirability guised as a “preference” is the most frequent. They assume that to be dark-skinned is to simply be withdrawn from people’s dating pool and overlooked when Valentine’s Day comes around. What people fail to realize is that colorism is a death sentence because to be dark-skinned is to be close to death, both material and social, in ways unimaginable.

It’s easy for people to read about colorism and collapse it into anti-Blackness, but even though all Black people experience anti-Blackness, we don’t all experience it the same. If anti-Blackness is the gun, colorism is a particular bullet.

For dark-skinned people, colorism means that there a higher chance of being seen as violent, which means that we can never be on the receiving end of violence, only the ones wielding it. Never a victim, always a perpetrator. This global understanding of dark skin results in a myriad of consequences, death being the most frequent. Dark-skinned people are more likely to encounter the police, and those encounters are more likely to land us in front of a judge or dead. And when it comes time for the judge to sentence us, the chances of us getting minimal sentences are slim, because who sees darkness and wishes for it to be free? In the moments that dark-skinned people find themselves in relationships, the chances of those relationships being abusive are higher because who chooses darkness and actually values it? Who chooses to dance with it, lovingly? For dark-skinned people that give birth, the chances of us dying during those moments are higher because who believes that the darkness should continue its’ lineage?

When Oluwatoyin Salau was murdered last year, it mattered that she had tweeted asking for refuge just days before her disappearance. It mattered that no one listened. It mattered that she was dark-skinned and her fear and later pain, were seemingly invisible.

Even in situations where death isn’t present, colorism is often veiled. It looks like never supporting your dark-skinned community. Never sharing their work. Never affirming their beauty. It looks like increasing your aggression towards them in light-hearted arguments. It looks like always asking them for emotional support while being emotionally void when they need it in return.

Colorism feels difficult to recognize because it so deeply embedded into our understanding of life. Outside of the context of the physical body, darkness is defined and associated with negativity, danger, aggression, and deviance. Even in language, we are defined and limited. How does one escape what is everywhere?

I wish I had grown up with the guidance to recognize my brilliance despite the world telling me that my darkness couldn’t hold it. I wish someone had told me that despite the design of this world, I am allowed to embrace my darkness, choose it willingly and celebrate it. I wish that someone would consistently remind the dark-skinned Black children that being dark is not the crux of their story.

The reality is that to recognize colorism in its’ totality, it’s important to deconstruct our biases. It’s important to recognize colorism as a facilitation of anti-Blackness rather than an enforcement of preferences. It’s this deconstructing that has the potential to shift the trajectory of someone’s life, someone’s ability to navigate surviving a death that will always await them. The more we are willing to recognize the reality that dark-skinned Black people, particularly Black trans, fat, or disabled people, endure a different type of violence due to the nuance of existing not only as Black but as dark, the less tension we’ll feel when addressing the nuances of anti-Blackness and how it permeates.